Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images News / Getty Images

November 9th, 2016

Understanding political movements is surely the modern equivalent of attempting to fathom the divine. They may simply be beyond human comprehension. Be that as it may, there are no shortage of prognosticators. In just the last three hours, I have read accounts that attribute Trump’s victory to racism, sexism, the disconnectedness of political elites, economic anxiety, third-party voting, Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, trade deals, and manufacturing. Michael Moore believes that the much-ignored suffering of working class Americans led them to find a convenient vessel for a longed for ‘political revolution.’ Numerous articles argue that the arguers themselves are the problem.

My own feeling – and that expressed by many of the rainy-day New Yorkers I saw today – is a numbness towards explanations. I’m just sad. Winning the way Trump did – the angry, belittling tweets; the banana-republic showmanship; the front-and-center bullying of his enemies – shows us how small is the correlation between decency and popularity.

But, on the whole, Americans still tend to be decent people. (And, as Joshua Rothman points out, decent neighbors.)

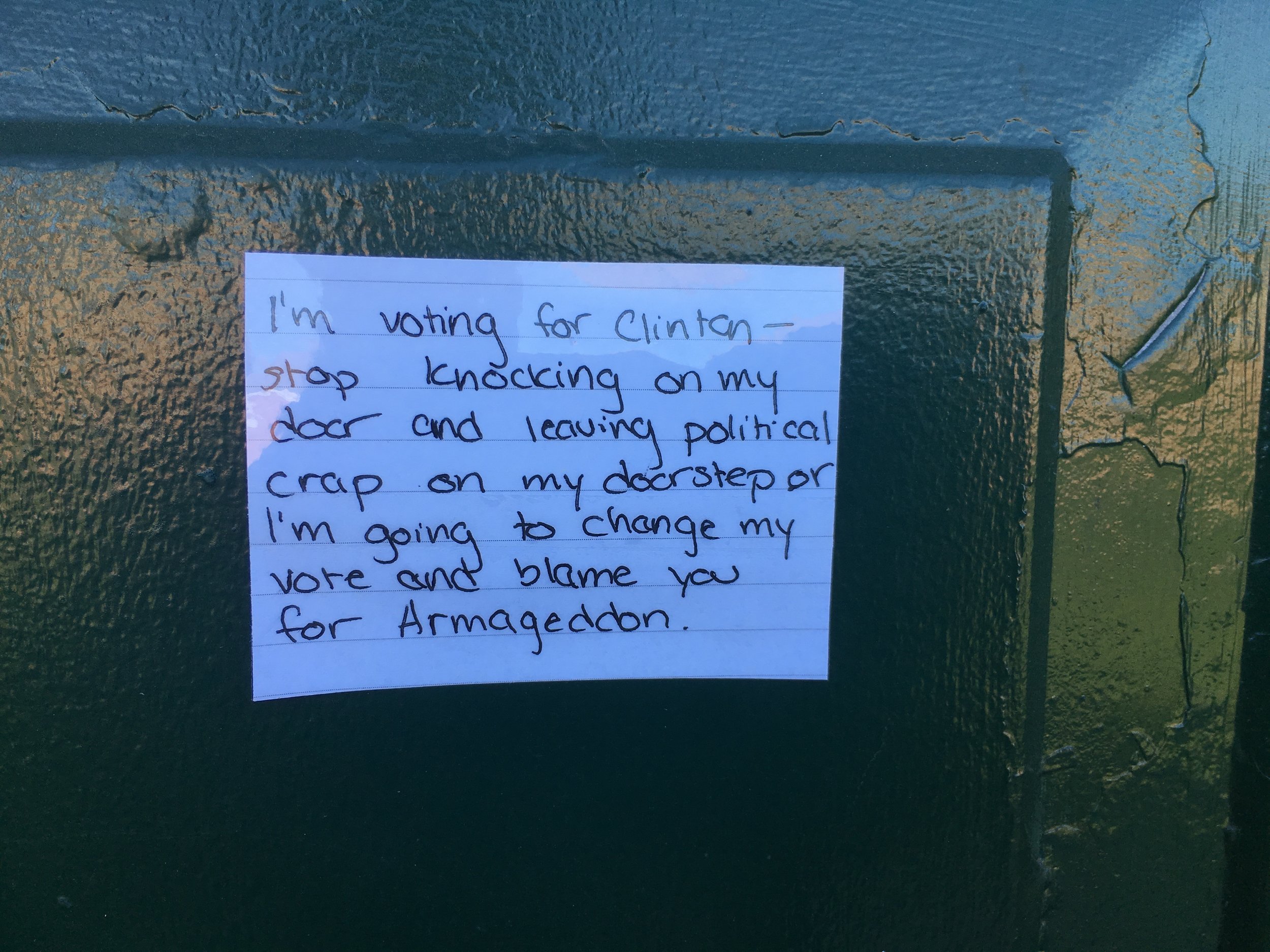

I spent the last three days before the election in Columbus, Ohio, where a lovely couple put me up in their guest room for a few days so that I might go around knocking on doors and encouraging people to vote for Hillary Clinton. In campaign speak this is known as canvassing. And the broader effort is known get out the vote or GOTV. I’ve worked on GOTV in one respect or another in seven elections now, almost always knocking on the doors of strangers in neighborhoods that were not my own.

Columbus was unseasonably warm this November and people raked red and yellow leaves from their yards in T-shirts and shorts. For whatever reason, the neighborhoods I visited – middle-income, poor, or wealthier – seemed to have a collective muffler problem. Cars clunked by in various states of disrepair, announcing their presence through low, sputtering grumbles, as if the city were plagued by a persistent, irksome infestation of lions.

Muffler issues aside, the neighborhoods I visited varied dramatically. In one set of low-income row houses, a gap-toothed white woman with a black eye answered the door with her four-year-old in hand. She said she might think about voting, though it was clear to both of us that she wouldn’t be leaving the house until her face healed. Down the street, I watched a domestic dispute unfold outside an apartment: a woman with a voice like steel wool screamed and punched her boyfriend telling him to “get the fuck out of here” until he picked her up and threw her into her car. She screamed at him, got into the driver’s seat, and tore off in her car (broken muffler) before I could call the police, but it seemed just as well. I couldn’t clearly tell who the abuser was. And a little girl down the street seemed nonplussed: “oh, they’re just having another fight.”

In a wealthier neighborhood, later in the day, I heard a different little girl yelling at a boy through an open window: “Ooh, you nasty. I know what you’re doing in there. Nobody pees for twenty minutes. You nasty.”

With the exception of brief interludes like these, knocking on doors was extraordinarily dull work. But the interludes can be lovely or exciting: in different elections over the years, I have been met at the door with lemonade (New Hampshire), cookies (Florida), and a loaded assault rifle (Wyoming). I’ve been given stock tips, photos of fetuses, and long exegeses on who, exactly, controls the banks.

Demographics and data play a heavy role in where you knock. The goal is to interact with low probability voters: people who are registered but don’t show up for every election. These people are distributed across neighborhoods and wealth groups, and this makes canvassing the physical equivalent of dialing random numbers from the phone book. It’s one of the rare times in modern life where you will see how complete strangers live without the voyeuristic filter of television.

Here is my overwhelming conclusion from eighteen years of canvassing: low probability voters just don’t give a shit about elections. Being political is a hobby. And it is a hobby that belongs to other people. Their own lives are much more concerned with fights and sports team and raising children. And these are the people on whom elections hinge. It’s as if we were to determine the pitching rotations of Major League Baseball teams by soliciting the opinions of bird watchers. It’s not that the decision making would necessarily be terrible. We just wouldn’t expect it to be wise.

One outspoken voter...

***

About a decade ago, the political commentator Mark Halperin came to an astonishingly obvious conclusion: maybe the process of running for office is not, in fact, a good proxy for determining whether a candidate will be any good at the presidency. It seems like a pretty self-evident proposition: of course campaigning and governing are different skills.

I mention this thesis not merely to point out its idiocy. I mention it because, in order to arrive at the conclusion that campaigning and governing don’t involve the same skill set, Halperin must have at some point believed that they did. He was a veteran reporter. He spent a lot of time thinking about politics. And yet, after years and years of following elections, his default assumption was that the skill set used to make stump speeches was a just and necessary way to determine whether a person ought to be allowed to start wars.

If Halperin believed that, why wouldn’t voters?

***

I tutor math. And perhaps because I tutor math, I keep thinking of this electorate with the same analogy: it’s like a kid who is mad at math. I’ve had students – not many, but some – who get actively angry at the idea that a fifteen percent increase is the same as 115% or 1.15 or one and three twentieths. They aren’t angry with me. Or with their teacher. They are mad at the math itself. It’s infuriating. So they take it out on me. Or their teacher.

***

On Sunday, after canvassing in the neighborhood with the back-and-forth bout of domestic violence, I spoke with another of the Clinton campaign volunteers: “it’s a tough case to make with these guys,” I said, “because the vote really isn’t going to affect their lives.” And I realized I’d made the same statement to a different volunteer back in 2002 in New Hampshire. The two places were a thousand miles and more than a decade apart, but they could have stood in for one another: the same broken plastic lawn furniture, the same newspaper-covered windows, the same chipped or shattered toys littering the lawns.

There was nothing in this Columbus neighborhood that would have looked out of place in 1996. The housing was the same, the furniture, even the roads. There were no physical details that anchored the neighborhood to the present. There is no place in New York or San Francisco where that is true. To be clear, there are policy differences that might genuinely make a difference to these people – paid parental leave, infrastructure investment and its concomitant jobs, increases in the minimum wage – but the byzantine political machinations behind the success or failure of those policies are too much for any voter to keep track of. And voting is far less urgent than the near-term worries about children, neighbors, and spouses. The immediate reality is this: large swaths of the country still exist in the mid-1990’s. And the voters there are mad at the math.

***

I don’t think that Michael Moore is right about the reasons for Trump’s election, at least not wholly. And not just because he has claimed that the electorate is feeling revolutionary every election cycle since 1996. I think Moore’s explanation fails because there are too many powerful nativist, right-wing movements across Europe for this to have a purely domestic explanation. Right wing resurgence seems like part of a broader global trend and voters in Germany are not motivated by central government neglect.

I think Jill Lepore and George Saunders come closer to hinting at what’s happening. We’ve become a culture of mobile-phone news with no common media. And for the first time in American history, we can organize most of our lives around the principle of never seeing anyone we disagree with.

So the best possibility of persuading the country to move in some progressive direction would be to actually meet face to face. Persuasion requires meeting. Particularly when fear is involved. In order to understand that someone is not an abstract monster, it helps if that person brings you cookies or lemonade. Or even if he is polite while he holds an assault rifle. But we’ve vilified our political opponents. And face-to-face meetings with those opponents have become vanishingly rare.

***

The problem with being angry with math is that math tends to win. Regardless of how much you yell at it, 115% will remain equivalent to one and three twentieths.

The things that would give jobs or purpose to the people in the hard-hit middle parts of the country are not coming back. The math prevents it. Textiles will continue to come from Asia. Corporations will continue to move where labor is cheapest.

The climate will change whether or not we believe in it.

So now I’m asking the same questions as all the other disappointed people: how did we get here? How can we change this? The bird watchers have put a little leaguer in to face off against the Cubs starting lineup. How do we make this less bad?

I can’t get over the the unwavering truth that most people I have met in this country are decent to strangers who show up unannounced at their doors. And yet we have just decided an election based largely on the premise that strangers are terrifying.

Realistically, urban and rural people are not going to have significantly more face time in the next four years than they did in the last. The Balkanization of news doesn't show any signs of slowing. In the first twenty hours after the election, some leftist friends took the opportunity of Clinton's loss to relitigate her FBI emails on my facebook page. The urge to be right on the internet has no relevance to political or personal consequences. And that also seems unlikely to change.

So I’m stuck. And I’m sad. I genuinely believe that the only plausible solution to the indecency of this past election is meeting face-to-face with people with whom we disagree. And I genuinely believe that there is no way that is going to happen on any kind of relevant scale.

And so, hypocrite that I am, the only thing I can think to do is sit alone, typing words into space: a secular prayer for lonely, like-minded people to read.